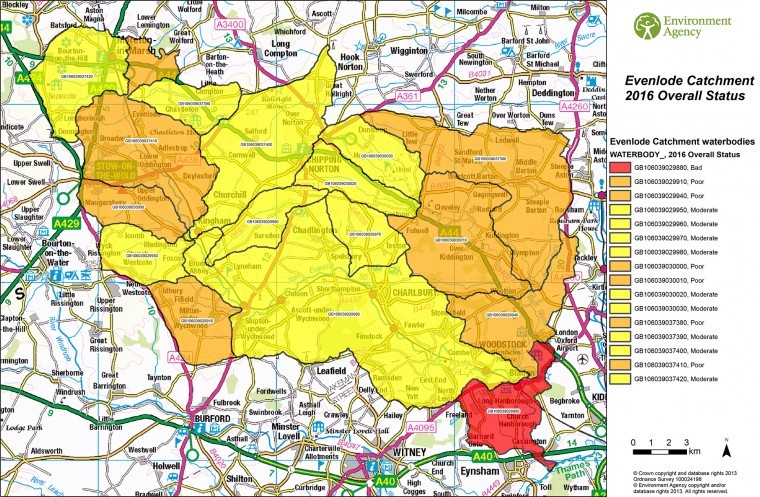

Applications for the cash closed in November, and the measures will be introduced from 1 January 2018 in a trial covering three areas of the Evenlode catchment, which goes across Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.

A catchment fund will make annual payments to support changes in operational practices on farms. Operational payments can be made for up to three years, and are subject to annual farm checks.

Payment options include £311 a hectare per year for arable reversion to grassland or other low phosphorous practices; £522 a hectare per year for a two year sown legume fallow; £353 per hectare per year for a six metre plus buffer strip using vegetation to intercept water, sediment and nutrients; and £512 a hectare per year for a 12 metre plus watercourse buffer strip and £557 a hectare per year for an in field grass strip to do the same thing. Taking small areas out of management attracts a payment of £370 a hectare per year. There will also be one off payments for measures such as outdoor concrete yard renewal and improving manure storage.

In addition to the catchment fund, Thames Water is offering an advice service to help farmers make the best of existing agri environment schemes. The service includes free farm visits to help reduce phosphorus loss and benefit land in other ways.

Thames Water will work with the Evenlode catchment partnership and other local organisations to provide river and wetland restoration schemes across the catchment. Farmers will also be asked to join a trial to explore the effectiveness of no till and cover crops to reduce the loss of phosphorus to watercourses.

From 2018, Thames Water will select the most effective parts of the pilot and roll these out across the wider Evenlode catchment.

High levels of phosphorus in river water can damage the environment, for instance by encouraging excessive weed growth and generating algal blooms. For this reason, limits for phosphorus concentrations in natural waters have been set to protect the environment.

Human and animal waste as well as fertilisers are the main sources of phosphorus in water. Water companies have historically relied on wastewater treatment to reduce concentrations of phosphorus before it reaches rivers. “This activity can be expensive, resource intensive and waste generating,” Thames Water said.

Sarah Olney has been seconded to Thames Water as the scheme’s agricultural adviser and has been a catchment sensitive farming officer since 2006. She and her husband farm between Cheltenham and Tewkesbury outside the catchment.

There has been an excellent response to the trial, Ms Olney said, with about 15 farms involved. “On each farm the solution to preventing phosphorus pollution is very different. But we have discussed everything from good soil management and the sound management of tussocky, unmown buffer strips to arable reversion in fields vulnerable to flooding, natural flood management and wetland schemes.”

One of the reasons the trial is popular was that the Rural Payments Agency is not involved with inspections. “We will make independent inspections and there will be monitoring in each of the three areas so that we can show farmers how much the pollution has reduced.”

She added that some farmers liked the Thames Water Grant scheme but others preferred the relevant options in the mid or higher tiers of countryside stewardship because this is a five year scheme with a guaranteed income. “I can signpost farmers to the different options as well as acting as a bridge between farmers and all the different organisations involved.”