New products being developed by a company in Hampshire to control pests in stored commodities such as grain have taken seven years to develop and is only now going through the annexe one registration of its active ingredient. That will take a minimum of 18 months, after which the products themselves – which promise to cut the use of conventional storage pesticides – will have to be approved, which could take another 18 months.

“Annexe one registration depends on a positive approval,” said Sue Harris, regulatory affairs manager at Exosect Ltd, which is working with CTGB in the Netherlands on the registration. CTGB is the Netherlands’ equivalent of the UK’s chemicals regulation directorate, which is part of the Health and Safety Executive. “There is no guarantee they will accept the submission.”

The registration process costs at least £250,000 and Ms Harris said it could be more if Exosect is asked to do more work to satisfy CTGB.

The time and expense taken to approve Exosect’s products illustrates how farmers can be left with few alternatives when the European Union removes products based on older chemistry. This is happening more and more as EU legislation such as the sustainable use directive (SUD) and the water framework directive make it harder to use conventional pesticides, herbicides and fungicides.

“The SUD permits the targeted use of integrated pest control,” Ms Harris said. “That includes low risk products such as biologicals and pheromones. Industry is under a lot of pressure from the government to develop these products and promote their use – and there are companies and investors who are happy to help.”

But Ms Harris added that organisations such as International Biocontrol Manufacturers Association are lobbying to reduce the time and cost taken to approve alternatives to conventional pesticides. “Many authorities and the European Commission are saying they could have a fast track system for low risk substances,” Ms Harris added. “This could include reduced data requirements and even subsidies for small companies which want to move into this area. But so far not very much has happened.” Ms Harris suggested that efficacy and toxicology could be reviewed quickly for low risk substances so they could be given a conditional status. “This would allow farmers and growers to use the products before they are given a final approval later. But that assumes the authorities have the right resources to make quick progress.”

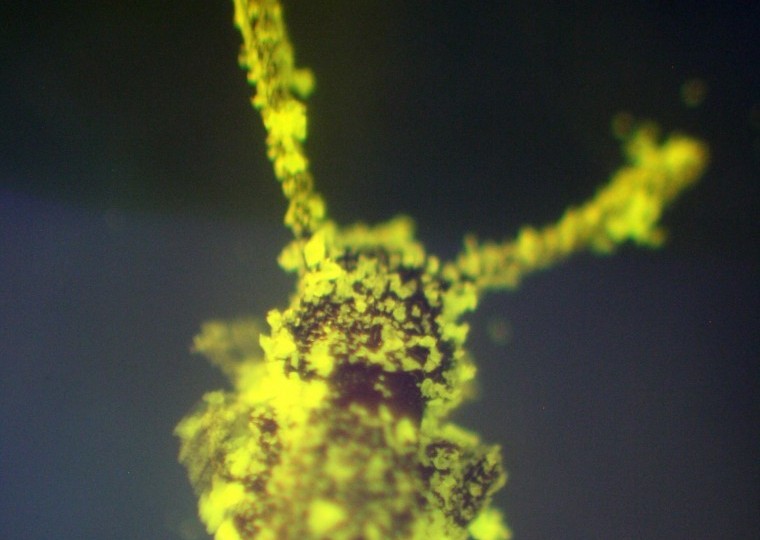

Exosect’s new active ingredient is a naturally occurring pathogenic fungus which is very host specific and targets beetles, other crawling insects and moths. Further down the line, two products will be aimed at grain pests: one is a surface treatment to reduce any infestation before the grain is stored, and the other is an admixture to control infestation in the grain itself.

These products are based on Exosect’s platform technology, an electrostatic powder called Entostat which sticks the fungal spores to the insects and infects them. Although Exosect used to develop its own products – such as those based on pheromones – the huge cost of registration and commercialisation prompted a move to licensing the company’s platform technology. “We tend not to take a product all the way through to commercialisation,” explained Georgina Donovan, Exosect’s communications manager. “We support other manufacturers wanting to register their active ingredients or formulations more effectively.”