Because there is a growing need for agricultural or renewable production of biofuels and other commodity chemicals to move away from fossil fuels, scientists have long sought to enhance the internal organisation of bacteria and improve the efficiency of the cells for making nutrients, pharmaceuticals and chemicals.

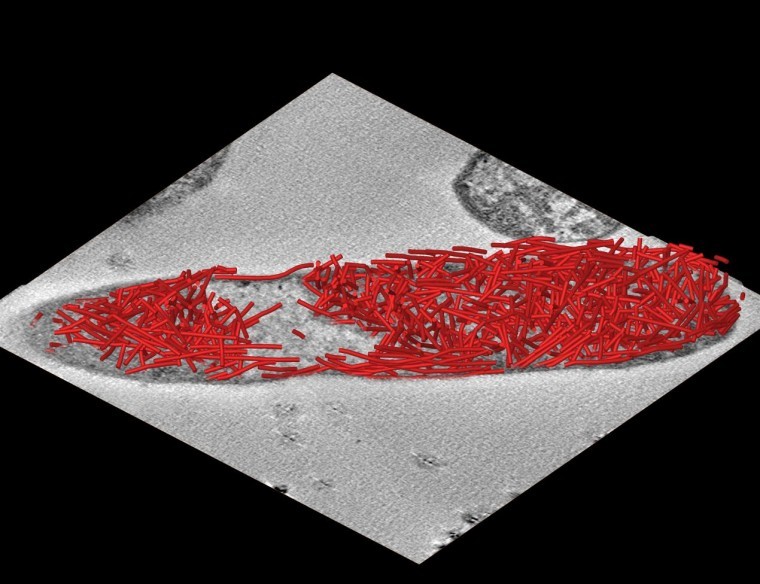

The research team, led by Professor Martin Warren at Kent’s School of Biosciences, working with professors Dek Woolfson and Paul Verkade at Bristol, found they could make nano-tubes that generated a scaffold inside bacteria.

With as many as a thousand tubes fitting into each cell, the tubular scaffold can be used to increase the bacteria’s efficiency to make commodities and provide the foundation for a new era of cellular protein engineering.

The researchers designed protein molecules and developed techniques to allow E. coli to make long tubes that contain a coupling device to which other specific components can be attached. A production line of enzymes could then be arranged along the tubes, generating efficient internal factories for the coordinated production of important chemicals.

Uitilising a form of molecular velcro to hold the components together, the team added one part of the fastener to the tube-forming protein and the other to specific enzymes to show that the enzymes can attach to the tubes.

By applying this new technology to enzymes required for the production of ethanol – an important biofuel – the researchers were able to increase alcohol production by over 200%.

This Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) funded collaborative project between the University of Kent, University College London and the University of Bristol entitled Engineered synthetic scaffolds for organizing proteins within the bacterial cytoplasm is now published in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.