The very dry weather and recent heavy rain is likely to lead to late outbreaks of lungworm disease (husk) in grazing cattle, caused by the Dictyocaulus viviparus parasite. Boehringer Ingelheim is urging cattle farmers to remain vigilant for signs of the disease, which can cause significant production losses and increased costs.

Sioned Timothy, ruminant technical manager at Boehringer Ingelheim says: “Lungworm larvae excreted onto the pasture early in the grazing season are likely to have remained locked within dungpats while temperatures were very high.

“While larvae on pasture will die in prolonged hot, dry weather, the residual moisture within dungpats means that larvae excreted recently are likely to have survived. Now that we have had widespread rainfall across the country, we expect to see larvae complete their development and disperse onto the pasture to infect grazing animals.”

Heavy rain is very effective at distributing infective larvae from pats, but the pilobolus fungus that grows on dung also plays an important role in this; propelling larvae up to three metres as it expels its own spores.

“While July, August and early September are usually the peak months for lungworm infections and cases of clinical disease, this year we expect to see infections later into autumn and, depending on the weather, as late as November.

The problem for farmers, and vets, is that lungworm can be difficult to diagnose at an early stage and may not be spotted until a full-blown outbreak occurs,” says Ms Timothy.

Clinical signs from late-season infections may not be observed until cattle are housed, and complicating matters further, coughing can be confused with other respiratory diseases, which can occur shortly after housing.

Sudden outbreaks of lungworm disease can be severe and, if the early signs of infection are not identified quickly, significant production losses – of up to £145 per animal1 – could occur, including death in the worst cases. Lungworm should always be considered as a potential cause of coughing in cattle. Farmers should not wait until the whole herd is unwell, but seek advice from their vet early in the course of disease to minimise long-term impact.

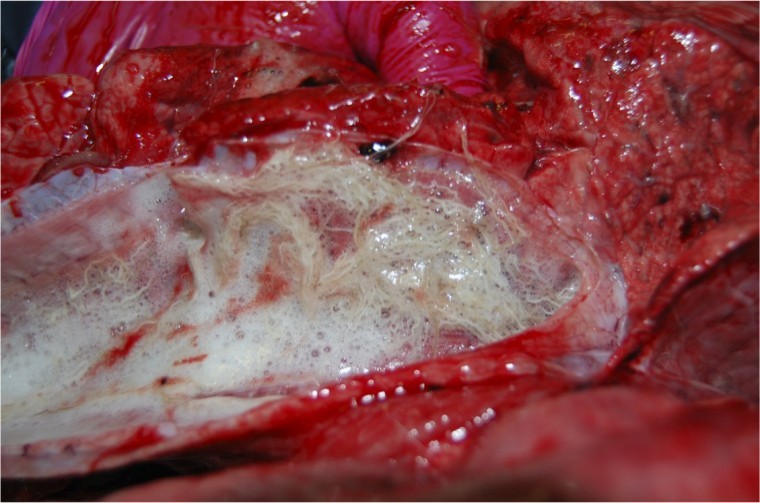

Other signs that can indicate lungworm infection include rapid loss of condition and sudden milk drop in lactating animals. Dairy cows will often spend less time grazing, and more time resting. Their water intake is also likely to be reduced. Severely affected cattle will typically stand with head and neck extended in an ‘air hunger’ position.

There is an increasing trend for adult cattle, as well as youngstock, to be affected by lungworm disease. Immunity to lungworm is short-lived, and if natural boosting through low-level exposure to larvae does not occur, animals may be rendered susceptible to disease when the number of larvae present on the pasture increases, as may be the case this season. However, even immune animals can succumb to disease in the face of high larval challenge.

If lungworm is diagnosed, cattle should be treated immediately with a wormer that quickly removes lungworm and prevents re-infection, to allow lungs to recover. It’s vital that the whole herd is treated as some infected animals will not show obvious clinical signs at the same time but will still suffer performance losses. A vet should assess severely affected individuals, as they may need additional treatment to treat pain, inflammation and any secondary infection.

Dairy and beef cattle can be treated with Eprinex Pour On, an eprinomectin pour-on wormer, with the advantage of zero-day milk withhold for dairy herds. Eprinex removes lungworm and a range of other parasites present in cattle in the autumn, including key gutworm species Ostergagia ostertagi and Cooperia, and prevents re-infection by lungworm and Ostertagia for 28 days and Cooperia for 21 days.