Dr Tim Potter, from Westpoint Farm Vets, part of the VetPartners group, explains the reasons behind the increased risk of oocysts and his recommendations to help keep calves healthy.

“As stocking densities increase pre-turnout, it’s harder to keep sheds clean and dry, so you generally see a spike in oocyst numbers in the environment and therefore a heighted risk of ingestion by calves,” he says.

He explains that coccidiosis is spread by faecal to oral transmission, so contaminated water troughs, dirty udders or sucking on dirty fences are all possible routes of infection.

“In addition to this, coccidiosis causing oocysts are sensitive to sunlight, so the dark corners in sheds can be a hotspot for oocysts, unless they’re decontaminated with an appropriate disinfectant,” says Tim.

“Problems can also arise at turnout. Oocysts can survive for up to a year, so if a field was contaminated in the previous season, it’s likely that the following year’s calves will become infected upon turnout.”

Spotting and treating coccidiosis early can help minimise impacts. Tim suggests looking out for calves that appear depressed, are eating less than usual, are not growing at the expected rate or have scour with fresh blood in it.

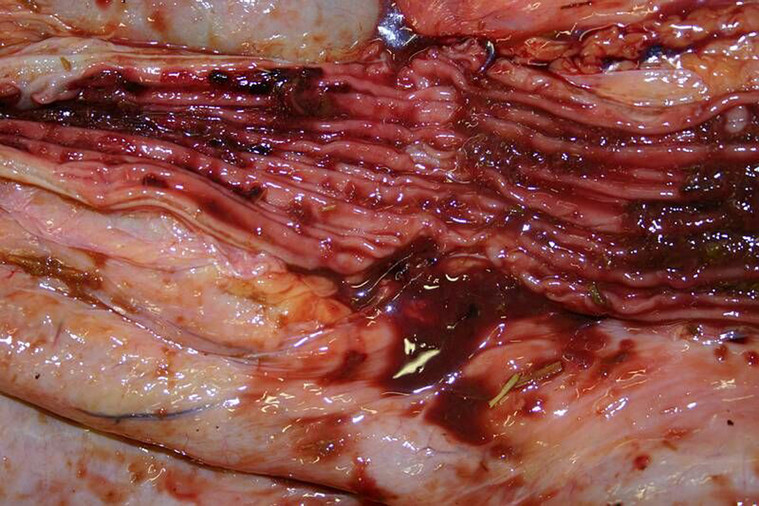

“Red blood in diarrhoea indicates that there’s damage to the lower digestive tract, and coccidiosis is a likely cause. You may also see calves with their tails up demonstrating unproductive straining, with perhaps some mucus being passed, which is due to irritation of the gut lining.”

Tim also emphasises the importance of considering farm history.

“If there was a coccidiosis issue last year, it may be worthwhile speaking to your vet about using a toltrazuril based product, such as Baycox®, to control the number of oocysts being shed into the environment before the risk period. Waiting to see signs will mean gut damage has already occurred by the time you treat.

“If you’re concerned about coccidiosis following an outbreak last year, I’d strongly recommend speaking to your vet to discuss the best approach for reducing risk on-farm. Similarly, if you’ve spotted symptoms then you’ll need to get in touch with your vet to get a diagnosis and identify the most appropriate treatment approach.”

Tim adds that it is important to treat all the animals in the same pen, even if only one or two are showing symptoms. “It takes between 15 and 21 days from ingestion of the oocyst to shedding of more oocysts in the faeces, so if one animal is showing symptoms it’s likely that more have already been infected.”

Picture: Damage to Gut lining