Agriculture’s ambitious plans to take the lead on tackling climate change were highlighted at this year’s South of England Agricultural Society’s (SEAS) farming conference.

The conference, which attracted a healthy online audience, was charged with considering whether or not UK agriculture could achieve a ‘net zero’ position on carbon in less than 20 years from now, and gave a generally upbeat response to the question.

It was NFU President Minette Batters, one of an impressive line-up of speakers brought together for the event, who reminded the virtual audience that the 2040 target – ten years ahead of the Government’s own 2050 deadline – had been put forward by, rather than being imposed upon, the industry.

She recalled that the earlier target had been agreed at the 2019 Oxford Farming Conference, adding that the announcement had “woken up” then Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Michael Gove, that year’s headline speaker.

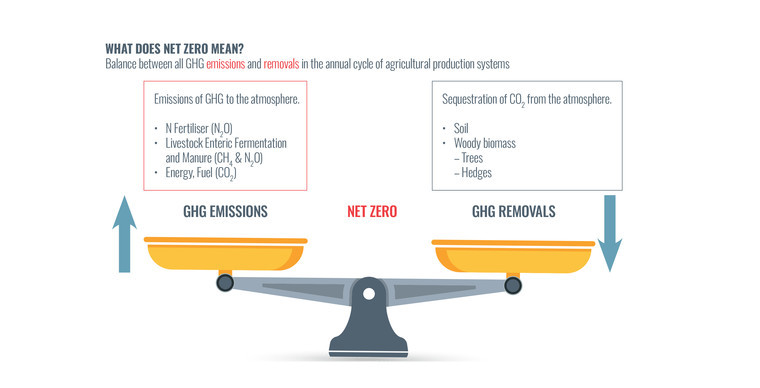

A number of the speakers at the SEAS conference, expertly chaired by BBC presenter Charlotte Smith, pointed out that as well as being a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions, UK agriculture was also in a strong position to come up with innovative ways of capturing carbon and reducing the amount of gasses released to the atmosphere.

There was also considerable debate around farmers’ and landowers’ ability to measure their net carbon impact on the environment, with no agreed mechanism in place to calculate the true figure.

Organic farmer and Nuffield Scholar Tim May, managing director of Kingsclere Estates, was particularly outspoken on the issue, pointing out that without a robust way of calculating carbon emissions, the industry could hit the target simply by manipulating the figures.

Another Nuffield Scholar, Doug Wanstall, who is working hard both to reduce the impact of his own farming practices and to help others through his Re-Generation Earth business, was clear on what was needed: “If a carbon market is to develop, we need a recognised way of benchmarking,” he stressed.

Ms Batters, who opened the conference, welcomed the Government’s decision to strengthen the role of the Trade and Agriculture Commission following a one million signature petition earlier this year. She said it was “crucial” to the net zero campaign for future trade deals to be sanctioned by the commission.

She added that “climate smart farming” was good for the industry, for the economy and for the environment and said that while 10% of the UK’s carbon emissions came from agriculture, farming acted as “both a source and a sink”. Farmers and landowners had been reactive for too long and now had a chance to lead the agenda, she added.

Ms Batters said farming needed to look at efficiency and productivity, finding ways to increase food production but doing so sustainably, using fewer inputs and reducing the impact on the environment. It also needed to look at ways of capturing more carbon, such as by planting more trees and hedges, she said.

Offering a vision of the UK as a world leader in climate change, Ms Batters said that leaving the EU was an opportunity for “smarter regulations” rather than fewer of them, and said the Environmental Land Management scheme would “definitely shape the future” by incentivising farmers to improve their practices.

In response to a question on promoting organic food, though, she said incentives were not the way forward and that growth in that sector needed to be market driven. Otherwise, she said, any subsidy would just lower prices.

Tim May stressed that farmers and landowners needed to look at their whole system rather than just focusing on a single issue, such as lowering their carbon footprint. He moved the 1000ha Kingsclere Estate in 2013 from predominantly arable to an organic mixed farming model which includes chickens, dairy, quinoa, pigs and sheep, aiming to use outputs from one area to support another in a ‘circular farming’ system.

“You can see it as a dung heap or as somewhere to grow pumpkins,” he commented.

Doug Wanstall’s Re-Generation Earth initiative acts as “a conduit between those companies and individuals that wish to take responsibility for their effect on the planet and those landowners that can do something about it”. The Ashford farmer also farms 1,100 acres of arable land and runs a free-range egg operation with 50,000 laying hens.

“We need to work with nature rather than against it,” he said, adding that being “sustainable” was not enough. “We need to be regenerative and resilient,” he explained, adding that UK farmers and landowners needed to be the backbone of the country’s new approach to tackling climate change.

Pointing out that his own farm currently sequesters 4,000 more tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) than it emits annually, he stressed the need for a carbon market and asked: “Who will pay for sequestered carbon?” He also suggested that growth in livestock should go hand-in-hand with increases in arable acreage so that nutrients could be used to improve the soil rather than being wasted or, in extreme cases, polluting watercourses.

Other suggested ways of reducing farming’s impact on the environment included growing more legumes, minimum tillage systems and reducing the use of nitrogen.

The final speaker, Head of Sustainability at Map of Ag Hugh Martineau, said he believed agriculture could achieve net zero but wondered how long the industry could keep it there. He pointed out that while agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions had remained relatively stable over the past 28 years, other sectors, particularly energy supply, had cut their emissions significantly.

Mr Martineau joined the calls for better measurement tools, saying the industry needed “accurate and consistent protocols for carbon stock change measurement”.

The speakers all agreed that gene editing to breed new plant strains was set to become an important new tool in the fight to cut greenhouse gas emissions, with Doug Wanstall suggesting there was a “bright future” for the technology in the UK.

Summing up the event, conference organiser and SEAS-sponsored Nuffield Scholar Duncan Rawson said: “The over-riding message was clear – the industry can achieve net zero by 2040, but it will require farmers to adopt new practices and government support that incentivises the right behaviours.”